Baptised: Huntly, Aberdeenshire, Scotland, 11 July 1828

Died: Auckland, New Zealand, 6 October 1908

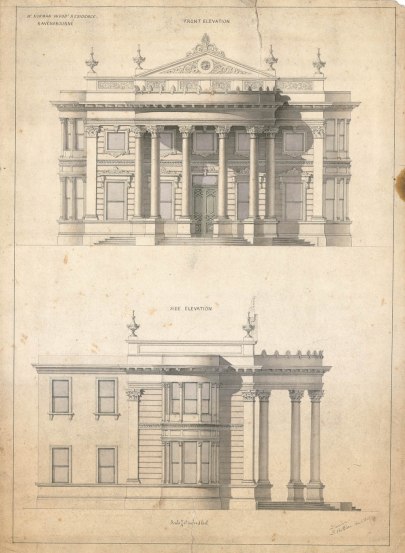

David Ross! Where to begin…? He’s a particular favourite of mine and the architect I’ve spent the most time researching. This partly comes from a love of his work, and partly from a feeling that his legacy has been neglected, and that he’s not nearly as well known as he should be. He is recognised by writers such as Knight and Wales as one of the most signficant architects to have worked in Dunedin, but very little has been written about him and there are no published articles (let alone books) devoted to him. As with a few of our Victorian architects, his Australian work is seen in isolation by Australians and his New Zealand work is seen in isolation by New Zealanders. I’ve made a list of over 450 building projects he worked on, so this post is very much the selected highlights.

Early life

Ross was born in Huntly, Aberdeenshire, where he was baptised on 11 July 1828. His father, William Ross, was a jeweller and watchmaker, and although I don’t know what sort of child young David was it’s easy to imagine him finding an interest in his father’s work that translated well into architectural studies. Ross began his career articled to the firm McKenzie & Matthews, of Elgin and Aberdeen, at about the time they designed such buildings as the Free Church College at Aberdeen and the Drumtochty Castle stables. Ross afterwards spent about three years working for Lewis Hornblower of Liverpool and John Hornblower of Birmingham, becoming ‘chief assistant’. Lewis Hornblower’s designs in Liverpool included the grand entrance and other buildings at Birkenhead Park (as part of a collaboration with Sir Joseph Paxton), and a commercial building at 25 Church Street (dating from a little after Ross’s time). He was best known for his later work on Sefton Park.

Victoria, Australia

Ross migrated to Victoria in 1853 and later that year went into partnership with R.A. Dowden in Melbourne. Their firm, Dowden & Ross, won the competition to design St Mary of the Angels Catholic Church, Geelong. It is not known which architect was primarily responsible for the competition entry, but following a fire in the 1868 Ross lost what he referred to as ‘my drawing of Geelong Cathedral’, and it seems he at least played an important role in the building’s design. Ross never saw the church in its completed state, as it took over 80 years to realise the original plans and the building was not finished until 1937.

![]()

St Mary of the Angels, Geelong. Photo (2007): Marcus Wong,

![]()

St Mary of the Angels, Geelong. Rear view. Photo (2007): Marcus Wong.

![]()

Wesleyan Church, Fitzroy Street, St Kilda, Melbourne. Photo (1933): J.A. Sears. State Library of Victoria. Ref: H20784.

![]()

Colonial Bank of Australasia, Kilmore. Photo (1861): Vanheems & Co. State Library of Victoria. Ref: H1819.

The Dowden & Ross partnership was dissolved in 1854 and Ross continued to practise on his own. His designs of the mid to late 1850s included Glass Terrace in Melbourne, the Chalmers Church at Eastern Hill, the Presbyterian manse at Williamstown, the tower and spire of the Scots Church in Melbourne, the Wesleyan Church at St Kilda, the Colonial Bank at Kilmore, the sea baths at St Kilda, and numerous houses and shops.

Ross married Agnes Buttery Marshall, the daughter of a prominent solicitor, in 1856. They had four daughters and one son. Tragically, the eldest daughter, Pameljeanie, died in 1860 at the age of three years.

Move to Dunedin

The family moved to Dunedin in May 1862, with Ross taking an office in Manse Street. Presumably, he was attracted by the building boom that accompanied the Otago Gold Rush. One of his first commissions was the Moray Place Congregational Church, which survives as the oldest church building in Dunedin (although it has been converted into residential apartments). Ross was for about five months in partnership with William Mason, who arrived a little later in 1862, but was soon working on his own again. He was a member of the first Dunedin City Council, from 1864 to 1865, and a glimpse of him in a cartoon shows a dark, bearded man, but frustratingly I’ve never found a photograph of him.

Ross received some notice as an artist. He showed nine watercolours at the 1854 Melbourne Exhibition, and more at a small Industrial Exhibition Dunedin in 1862. Some of his watercolours of Otago scenery were described in the Bruce Herald in 1874, with Ross reported to have ‘powers of landscape delineation… far beyond anything we had conceived in the way of local talent to exist in Otago’.

Early Dunedin works included the Bank of Otago in Princes Street (where the National Bank now stands) and the old Empire Hotel (on a different site from the current one). In the Mason & Ross partnership he probably designed the house Highlawn in collaboration with its owner, C.W. Richmond. He was also responsible for Colinswood, a more modest residence built at Macandrew Bay for James Macandrew. In some of these buildings a row-of-circles decorative motif can be seen, and although others used this, it is a distinctive Ross signature. Also typical of Ross is a particular style of paired round-headed windows.

![Congregational Church, Moray Place. Later changes include the side vestry, the front steps and entrance (moved from the side), the pinnacles, and rendering of the brick.]()

Congregational Church, Moray Place, Dundin. The later changes to Ross’s original building include the side vestry, the front steps and entrance (moved from the side), the pinnacles, and the rendering of the exterior brickwork.

![]()

Fernhill, Dunedin, built for John Jones. Photo (n.d.): Unknown. Hocken Collections. Ref: S12-282b.

![]()

Colinswood, Macandrew Bay. Photo (n.d.): James R. Cameron. Alexander Turnbull Library. Ref: 1/2-024931-G.

![]()

Elderslie, North Otago, built for John Reid. Photo (1905): Otago Witness. Hocken Collections. Ref: S12-282d.

Public buildings

In 1869 and 1874 Ross won significant commissions for public buildings. His Atheneaum in the Octagon survives, though stripped of its facade detailing. The statuary was the only feature in the engraving shown here that was never realised. His original portion for the Otago Museum also remains but the northern and southern wings were never completed to his design and suggested statuary and friezes were never added. As planned, it would have completed an exuberant design combining Greek revival and ‘Second Empire’ architecture. When it was finally decided to add the Hocken Wing to the museum in 1907, an elderly Ross wrote: ‘it was understood that for any future additions required to complete the design that I would be the Architect and paid as usual according to the cost. This being the case no other person should be allowed to interfere with my work without my permission’. He did not get the work but architect J.A. Burnside based his facade designs on Ross’s concept. The later Fels wing is different in scale and style, with a decision made to reorient the complex towards the Museum Reserve.

The Otago Education Board was the source of much work in the 1870s and Ross designed schools at Mosgiel, Allanton, Popotunoa, Port Molyneux, Sawyers Bay, Forbury, and Port Chalmers. He also designed large additions for Otago Girls’ High School (after they took over the boys’ building), the Otago Boys’ High School rectory, and the large Normal School and Art School building in Moray Place. He also found government work designing immigration barracks at Dunedin, Oamaru, Stewart Island, Bluff, Riverton, and Milton.

![]()

Athenaeum, Octagon, Dunedin. Samuel Calvert engraving (1870) from Illustrated Australian News. State Library of Victoria. Ref: IAN16/07/70/132.

![]()

Otago Museum, Great King Street, Dunedin. Engraving (1875) from Illustrated Australian News. State Library of Victoria. Ref: IAN24/03/75/44.

![]()

Gallery inside the Otago Museum. Photo (1890): Edgar Richard Williams. Alexander Turnbull Library. Ref: 1/1-025834-G.

![]()

Normal School and Art School, Moray Place, Dunedin. Private collection.

![]()

Port Chalmers Grammar School. Photo (n.d.): Unknown. Hocken Collections. Ref: S12-658g.

Commercial work and patronage

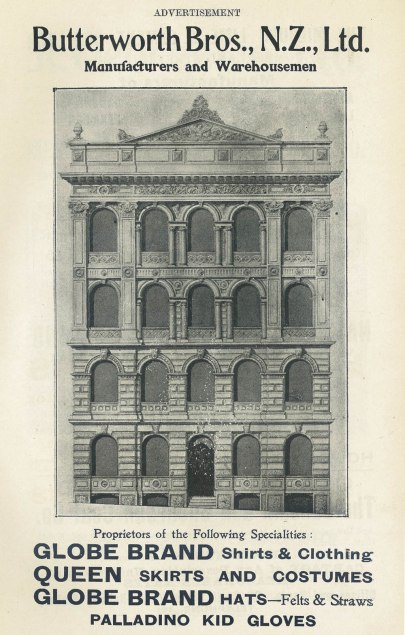

Among his private clients, Ross enjoyed the patronage of some of Dunedin’s leading businessmen. One of these men was Maurice Joel, for whom Ross designed a private residence (Eden Bank House), a shop in Princes Street, various additions to the Red Lion Brewery, the Captain Cook Hotel, and possibly the Caledonian (later Rugby) Hotel. For Bendix Hallenstein he designed two large clothing factory buildings in Dunedin and stores in Queenstown. He was also the architect of one New Zealand’s largest industrial complexes, Guthrie and Larnach’s New Zealand Hardware Factory buildings in Princes and Bond Streets, which was destroyed by fires in 1887 and 1896. Private houses included ‘The Willows’ (the house of Sir William Barron at Kew) and two North Otago homesteads: Elderslie and Windsor Park. His largest hotel was the Prince of Wales in Princes Street. In some projects he collaborated with his nephew, F.W. Burwell, who established himself in Queenstown and Invercargill and became one of the leading architects of southern New Zealand.

![]()

Eden Bank House, Regent Road, Dunedin. Photo: S. Collins. Hocken Collections. Ref: S12-549c

![]()

Guthrie & Larnach premises, Princes Street, Dunedin. Photo (n.d.): J.W. Allen. Hocken Collections. Ref: S06-152d.

![]()

Guthrie & Larnach premises, Bond Street, Dunedin. Engraving f(1877) from Australasian Sketcher. State Library of Victoria. Ref: A/S12/05/77/28.

![]()

Hallenstein’s New Zealand Clothing Factory (seen here as the National Insurance building). The Exchange, Dunedin. Photo (c.1930): Tourist and Publicity. Alexander Turnbull Library. Ref: 1/1-006149-F.

![]()

Hallenstein’s New Zealand Clothing Company offices and factory, Dowling Street, Dunedin. Photo (1880s): Burton Bros. Hocken Collections. Ref: AG-295-036/003.

Churches

Ross designed fewer churches in Otago than he did in Victoria, which probably owed something to R.A. Lawson’s monopoly on Presbyterian Church work and F.W. Petre’s on Catholic commissions . One of Ross’s buildings was the Presbyterian Church at Palmerston, with its distinctive rust-coloured Waihemo stone and very Scots-looking design, with a spire remiscent of both St Nicholas’ Kirk, Aberdeen, and his own Scots’ Church tower in Melbourne. The lines of the Palmerston church were later a bit muddled by the insertion of a large memorial window. Ross also designed Presbyterian churches at Balclutha and Clinton (both timber) and a Primitive Methodist Church at Bluff. His biggest commision was for Dunedin’s Knox Church. The foundation stone for this building was laid on 25 November 1872 but Ross was dismissed for misconduct on 16 January 1873 and his design was abandoned. He sued the church for wrongful dismissal and won on some points, but the verdict was mostly in favour of the defendants. Ross had purchased Bacon’s quarry, which it had been previously agreed would supply stone for the project, and the jury found that Ross’s actions in connection with this had been improper, but were not sufficient grounds for dismissal. The more significant issue was that he had selected a Clerk of Works, John Hotson, who was widely thought to be a drunkard and was found to be unfit for his job. Ross’s insistence on retaining Hotson and his refusal to acknowledge the replacement selected by the church was found by the jury to be reasonable grounds for dismissal. Ross was awarded a mere two pounds in compensation when he had claimed over £200. He was replaced by R.A. Lawson, who used his own more expensive design for the church.

This was not the only event that suggested Ross could be difficult to work with. In 1872 he unsuccessfully sued Vincent Pyke for fees he claimed were due for calling tenders for a house that was not proceded with. One witness, a contractor, claimed that ‘Some contractors refused to tender for any work under Mr Ross, and said they would rather do it for anyone else in the country. Witness did not know their reason for it, but he supposed it was over-vigilance on the part of Mr Ross.’

![]()

Palmerston Presbyterian Church.

![]()

Clinton Presbyterian Church. Photo (n.d.): Unknown. Hocken Collections. Ref: S12-282c.

Concrete

The first mass concrete buildings in Dunedin were built in the early to mid 1870s and Ross was at the forefront of this new technology, being slightly ahead of other local concrete pioneers such as N.Y.A. Wales, Lawson, and Petre (the last of whom was famously nicknamed ‘Lord Concrete’). In 1870 Ross and Burwell applied for a patent for sole use of ‘certain inventions and improvements in the construction of frames or apparatus’ for concrete construction. Another curious invention of Ross’s was a ‘self acting’ toilet seat, that lifted without being touched!

Ross was designing buildings in concrete from at least 1872 and in 1874 it was reported in the Otago Daily Times that ‘Mr Ross claims no originality in the matter, but credit must be given him for the persevering way in which he has hitherto quietly advocated the introduction of the new mode of building into the Province, and his efforts appear to be now beginning to be crowned with success, he having orders in hand for designing about 40 concrete buildings.’ These buildings included numerous workers’ cottages, a two-storey house, shop buildngs, and a grain store. The largest was the Otago Museum, in which Ross experimented by using old rails from railway lines as girders, a technique he further developed when rebuilding his Octagon building. An experimental concrete roof on the colonade on the Lawrence court house was spectacularly unsuccessful when the builder (who had been dubious about the design) removed his props and the whole thing collapsed. A replacement built to a revised plan remains in place today. In 1907, when technology for reinforced concrete construction was rapidly developing, Ross was proud that his concrete buildings had lasted well and claimed that no reinforcing was required in ordinary concrete structures, suggesting that he had fallen behind modern thinking.

The Inspector of Works for the museum was Edmund M. Roach, a fellow architect who supervised the construction of many of Ross’s designs and eventually became his associate. When Ross left Dunedin Roach took over his practice and for many years continued to manage his interests in the city, also acting as the executor of his estate.

![]()

Court house (Warden’s Court), Lawrence. The top storey is a later addition.

![]()

Crescent (now Careys Bay) Hotel.

![Prince of Wales Hotel, Princes Street, Dunedin.]()

Prince of Wales Hotel, Princes Street, Dunedin.

![]()

Ross’s own house in Heriot Row, Dunedin.

![]()

Chapman’s Terrace, Stuart Street, where I lived for two years. The building, which is currently getting a makeover, originally had a balustraded parapet.

Travels and family

Ross left New Zealand for an extended trip overseas in 1879 and 1880, visiting the United States and Europe. In London he was admitted a Fellow of the Royaly Institute of British Architects (FRIBA), a high honour that no other Dunedin architect received. He was nominated by John Norton, Robert Edis, and William Audsley. These were distinguished architects (Norton particularly) and Audsley would have known Ross from the years they both worked in Elgin and Liverpool. Burwell also became fellow in 1880, and in 1884 Ross and Burwell were the only architects in New Zealand to hold this distinction. Ross always used the letters ‘FRIBA’ in his later advertising. During his absence, Ross’s own buildings in the Octagon were severely damaged by fire. He had them rebuilt, with the top mansard floor replaced with another masonry storey added to the facade. Ross’s great sadness during this period was the death of his eight month old son, William, at Courbevoie, near Paris.

Ross separated from his wife, who later lived with her daugther in Yokohama, Japan, where she died in 1894. The couple’s elder surviving daughter, Flora, married Marc Lucas in Yokohama in 1894. The other daughter, Agnes, married Professor W.E.L. Sweet at Kumamoto in 1904. The presence of the family in Japan explains why some sources mistakenly state that Ross spent his later life in that country. Another interesting family connection was that Ross’s brother, Rev. Dr William Ross, was a Presbyterian minister in the West Indies and Lancefield, Australia.

Jobs in Dunedin in the early 1880s included Chapman’s Terrace in Stuart Street, Ross’s own house in Heriot Row, and the second Hallenstein factory. One of Ross’s last Dunedin projects was the head office building for the Union Steam Ship Company in Water Street, completed in 1883. Its richly decorated renaissance revival facade was made particularly distinctive by its dome (an observation post) and a collection of small minarets along the parapet. This decoration was removed in 1940 as part of remodelling carried out for the National Mortgage and Agency Company.

Auckland

In 1883 Ross won the competition for the Auckland Harbour Board Offices in Quay Street, Auckland, with a design that at first glance looks like a cheeky replica of the USSCo. building. The main differences were variations to the ornamentation and fenestration (including round-headed windows instead of square-headed ones on the first floor). Like its sister, this building suffered drastic twentieth century remodelling before its eventual demolition. The Harbour Board commission took Ross to Auckland where he was based from 1883 to 1886. It is perhaps unsurprising that he did not return to Dunedin, as there was little building work going on here in a depressed economy. Other architects who left during the 1880s included Maxwell Bury, Louis Boldini, and R.A. Lawson.

Among Ross’s more remarkable Auckland works there were additions for Alfred Isaacs which transformed his house Charleville into a fantastic but quite ungainly mansion with an enormous castellated tower that commanded superb views. He also designed substantial additions to the Star Hotel in Onehunga, and a large warehouse for Bell Brothers in Wyndham Street.

![]()

Octagon Buildings, Dunedin. Photo (1880s): Burton Bros. Alexander Turnbull Library. Ref: Ref: 1/1-006149-F.

![]()

Union Steam Ship Company offices, Water Street, Dunedin. Photo (1880s): Burton Bros. Hocken Collections. Ref: S10-221c.

![]()

Spot the difference! Auckland Harbour Board Offices, Quay Street, Auckland. Photo (n.d.): Henry Winkelmann. George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries. Ref: 1-W890.

![]()

Charleville, residence of Alfred Isaacs, Remuera, Auckland. Photo (c.1910): William Archer Price. Alexander Turnbull Library. Ref: 1/2-001180-G.

Australia again

In 1886 Ross left for Australia, setting up an office at Temple Court, Queen Street, Sydney. His best known work there is the St George’s Hall, Newtown, of 1887, which was one of his more grand and florid renaissance revival designs. Also from this period were the mansion Iona at Darlinghurst, and the masonry towers and other work for the Long Gully suspension bridge, which cost over £100,000 to build and was one of the largest bridges of its kind in existence.

Ross briefly practised in Wellington from 1893 before moving to Perth in 1895, where he went into partnership with Burwell. The partnership didn’t last long as Burwell soon set up on his own at Fremantle, but Ross remained in Perth for over seven years, getting some substantial residential commisions but probably less work than he would have liked. The most ambitious project he was involved with there was a proposed 1,160-seat theatre for Perth Theatre Company, but this never came to fruition. Other projects included villas for John Shadwick, F. Cairns Hill, and Stanley Sutton, and buildings for the Silver Pan Confectoney Company.

Ross’s most surprising move came in 1903, when he left Perth for Johannesburg, South Africa, where rebuilding had started following the Boer War. It was surprising not only because of the distance, but because Ross was approaching 75 years of age. A farewell event was held at the West Australian Club, where it was said that by his genial disposition Ross had made a large circle of friends, and was looked upon with much affection and goodwill: ‘Mr. Ross was not a young man, but had plenty of “go” and true grit and, would have ample scope for his capabilities in a new land with such possibilities as South Africa’. Ross feelingly replied, commenting that ‘he had always helped younger professional men without jealousy, and no thing pleased him better than when he saw any of the improvements which he had made adopted in general use. His ideas were not due to inspiration, but were the result of hard study.’

![]()

St George’s Hall, Newtown, Sydney. Photo: Hall & Co. State Library of New South Wales. Ref: 35195.

![]()

Long Gully bridge, Sydney. Photo (n.d.): Henry King. Powerhouse Museum Collection. Ref: 85/1285-1131.

Final years and conclusion

I have so far been unable to trace any of Ross’s work in South Africa, but he remained there until 1906, when he moved back to Auckland. It was there that he died on 6 October 1908, at the age of 80. Fellow freemasons from Lodge St Andrew arranged a funeral procession to the Waikumete Cemetery, where he was buried. The grave is unmarked. Ross had continued to work until the month before his death, with one of his last works being additions to St Barnabas Church, Mount Eden. Two daughters outlived him.

Ross would probably be more celebrated if he hadn’t moved around so much. He was soon almost forgotten in Dunedin, and in his own lifetime the Cyclopedia of New Zealand stated that he had been dead for several years. His New Zealand Historic Places Trust biography still states that he probably spent his later life in the USA and Japan, and some Australian sources give his place of death as South Africa. The fact that he is not identified as the author of many of his surviving buildings has prevented full recognition of his achievements.

Despite a lack of knowledge or writing about him, Ross has long been recognized as a key figure. His importance has been acknowledged by writers from the 1960s onwards (perhaps beginning with McCoy and Blackman’s Victorian City of New Zealand), and Knight and Wales describe him as ‘undoubtedly one of the most important architects who have worked in Dunedin’. Seven of his buildings are listed as Historic Places, partly due to their association with him.

Stacpoole (1971) wrote that ‘Quite clearly, [William] Mason was the architectural superior’ of Ross, and that where ‘Ross’s buildings are essentially Victorian, Mason’s display earlier influences and, to that extent, please us more today’. I agree that the two men often use the stylistic language of different generations, but disagree with the overall assessment. Mason designed two superb Dunedin buildings (the Post Office/Stock Exchange and Bank of New South Wales) but his other work (even including the 1865 exhibition buildings and St Matthew’s Church) doesn’t appear to give him any great claim to be ‘superior’.

In my opinion Ross was also of similar ability to his slightly younger contemporary, R.A. Lawson, who is recognised as Dunedin’s pre-eminent Victorian architect for designing the city’s grandest landmarks of the period (First and Knox churches, the Municipal Chambers, Otago Boys’ High School, Larnach Castle). In some particular aspects, such as commercial architecture, Ross’s legacy is no less significant than Lawson’s. His role as an innovator also give him a key place. What I most like about Ross though, is his knack for strong yet elegant, and rich yet unfussy design. I think his reputation will continue to grow.

Selected works:

- 1854-1856. Glass Terrace, Melbourne*

- 1854-1937: St Mary of the Angels Catholic Church, Geelong*

- 1855. Chalmers Church, Eastern Hill*

- 1856-1857. Presbyterian manse, Williamstown, Melbourne*

- 1856-1857. St Kilda Sea Bathing Establishment, Melbourne

- 1857. Tower and spire, Scots Church, Melbourne

- 1857. Flint, Ramsay & Co. warehouse, Collins Street, Melbourne

- 1857-1858. Wesleyan Church, Fitzroy Street, St Kilda, Melbourne*

- 1859. Colonial Bank, Kilmore*

- 1862-1863. Imperial Hotel, Princes Street, Dunedin* (attrib. only – much altered)

- 1863. Provincial Hotel, Port Chalmers

- 1864. Congregational Church, Moray Place, Dunedin*

- 1864. Empire Hotel, Princes Street, Dunedin (extensive additions)

- 1865. Bank of Otago, Princes Street, Dunedin

- 1867. Fernhill (Jones residence), Dunedin*

- 1867. Colinswood (Macandrew residence), Macandrew Bay*

- 1869-1870. Athenaeum and Mechanic’s Institute, Octagon, Dunedin*

- 1870. Rectory, Otago Boys’ High School, Dunedin

- 1872-1873. Windsor Park homestead, North Otago*

- 1873-1874. Elderslie homestead (Reid residence), North Otago

- 1874. Port Chalmers Grammar School

- 1874. NZ Clothing Factory, Rattray Street, Dunedin*

- 1874-1875. Court house, Lawrence*

- 1874-1876. Normal School, Moray Place, Dunedin

- 1874. Crescent Hotel (later Careys Bay Hotel), Careys Bay*

- 1874. Eden Bank (Joel residence), Dunedin

- 1874-1877. Otago Museum, Great King Street, Dunedin*

- 1875. Colonial Bank (later BNZ), Outram*

- 1875-1876. A. & T. Inglis, George Street, Dunedin* (mostly demolished)

- 1875-1878. Guthrie & Larnach, Bond and Princes streets, Dunedin

- 1876. Presbyterian Church, Palmerston*

- 1876-1877. Gridiron Hotel, Princes Street, Dunedin

- 1876. Terrace for Dr Murphy, York Place, Dunedin*

- 1876. Prince of Wales Hotel, Princes Street, Dunedin*

- 1876-1880. Octagon Buildings, Dunedin*

- 1877. Charles Begg & Co., Princes Street, Dunedin

- 1877. The Willows (Barron residence), Kew, Dunedin

- 1881. Villa for David Ross, Heriot Row, Dunedin*

- 1881-1882. Chapman’s Terrace, Stuart Street, Dunedin*

- 1882-1883. Presbyterian Church, Clinton

- 1882-1883. NZ Clothing Factory, Dowling Street, Dunedin*

- 1882-1883. Union Steam Ship Co. offices, Water Street, Dunedin*

- 1883-1885. Auckland Harbour Board offices, Quay Street, Auckland

- c.1883-1885. Additions to Star Hotel, Onehunga*

- 1885. Bell Bros warehouse, Wyndham Street, Auckland*

- c.1885. Charleville (Isaacs residence), Remuera

- 1887. St George’s Hall, Newtown, Sydney*

- 1889. Iona, Darlinghurst, Sydney*

- 1892. Towers, Long Gully Bridge, Cammeray, Sydney*

- 1899. Villa for John Shadwick, Colin Street, Perth*

- 1902. Villa for F. Cairns Hill, Subiaco, Perth

- 1903-1906. Various unknown works, Johannesburg, South Africa

- 1908. St Barnabas Church, Mt Eden, Auckland (additions)*

*indicates buildings still standing

References available on request

![]()

![]()